Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through them, we may earn a small commission and you support our blog to write more helpful articles – at no extra cost to you.

As Laos is a tropical country, there are obviously also Mosquito-borne diseases present in the country. Laos is rich in rivers, forests, and wildlife, which makes it also a home to mosquitoes that carry diseases such as Dengue Fever, Malaria, Chikungunya and Japanese Encephalitis. Whether you’re a traveler, digital nomad or long-term expat, it’s crucial to understand the risks and take simple, effective precautions.

Some of the mentioned diseases are spread all over the country, while some of them only affect certain areas. In this article I would like to give fellow travelers an overview of the different mosquito-borne diseases, vaccines (if available) and how to effectively protect against them.

In this guide, you’ll learn:

What mosquito-borne diseases are common in Laos

How to recognize symptoms early

Which regions are higher risk (and when)

The best prevention strategies

What to do if you get sick

Mosquito-borne diseases are still a risk to public health in Laos. But also for tourists, expats and digital nomads living or traveling in Laos, should be aware of the situation.

To combat the rise of mosquito-borne diseases the World Mosquito Program (WMP) began its work in Vientiane in 2022. Dengue is endemic in Laos and peaks during the rainy season (May to October), with over 39,000 cases in 2019, including 10,813 in Vientiane alone. The Chanthabouly and Xaysettha districts in Vientiane have been identified as priority areas due to high case numbers.

In collaboration with the Lao Ministry of Health and Save the Children, the WMP is implementing a pilot project involving the release of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, a proven and natural method to block disease transmission.

Wolbachia is a naturally occurring bacterium found in many insects, but not in the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which spreads dengue, Zika and chikungunya. Scientists discovered that when Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are infected with Wolbachia, the bacteria block the viruses from growing inside the mosquito. As a result, the mosquito can no longer pass the virus to humans when it bites.

Not all mosquitoes are the same. The danger lies not just in the itchy bite, but in what type of mosquito is biting you. Diseases like Dengue Fever, Malaria, Chikungunya and Japanese Encephalitis are each spread by different mosquito species, each with their own habits.

The Aedes mosquito, active during the day, is responsible for dengue fever and chikungunya.

Anopheles mosquitoes, which bite mostly at night, transmit malaria.

Meanwhile, Culex mosquitoes, also night-biters, are the main carriers of Japanese encephalitis. Understanding when and where each mosquito is active is key to protecting yourself effectively.

Laos is home to several mosquito-borne diseases, like everywhere in Southeast Asia. The most common being dengue fever, which occurs mostly during the rainy season because of the population increase of the Aedes mosquito. Malaria is still present, but only in some remote, forested areas, though the risk is low in cities and tourist regions. Chikungunya, a virus with symptoms similar to dengue, has also been reported, but is not common. In rural and agricultural areas, especially those with rice fields and pigs, Japanese encephalitis can be a risk, particularly for long-term visitors or people living in such rural regions. Each disease is transmitted by a different mosquito species, making awareness and prevention essential for travelers and residents alike.

While some people might think that Malaria is the number one disease transmitted by mosquitos in Laos, it is not! Dengue fever is the most common mosquito-borne disease in Laos and in general in the whole region of southeast asia. There are seasonal outbreaks of Dengue fever in Laos. More cases occur when the Aedes mosquito type is more active, like during the raining season from May to October, which makes Dengue fever endemic in Laos. Meaning that it is always present, but with major spikes of infections during warmer and wetter months.

According to the Lao News Agency, Laos recorded 556 dengue cases between January and March 2025, with no fatalities, marking a 70% decrease compared to the same period in 2024 (1,837 cases and 3 deaths). The highest number of cases occurred in Vientiane (152), followed by Luang Namtha (91) and Luang Prabang (66).

In response, the Ministry of Health has urged continued vigilance ahead of the rainy season and launched a nationwide campaign involving the release of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes. This innovative program aims to reach over 1.2 million people in high-risk provinces, including Vientiane, Luang Prabang, Oudomxay, Savannakhet, and Champasak.

Authorities remain optimistic that this approach will help further reduce dengue transmission and protect the population from mosquito-borne diseases.

Dengue is caused by the dengue virus (DENV), which has four different serotypes (DENV-1 to DENV-4). It is transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is active during the daytime, especially in the early morning and late afternoon. These mosquitoes breed in stagnant water, such as flower pots, buckets, old tires and even bottle caps, mostly in and around homes and urban areas. A second infection with a different serotype of the virus increases the risk of severe dengue.

I was infected with dengue fever once myself. The transmission happened in Koh Tao, Thailand. I felt many of the below mentioned symptoms and went to see a doctor. He did a blood test and confirmed that it was dengue fever. All you can do is take painkillers, such as Paracetamol (no Ibuprofen or Aspirin), drink plenty of water and electrolytes and try to sleep.

Symptoms usually appear 4 to 10 days after the bite and can range from mild to severe. They include:

In some cases, the disease can progress to severe dengue (also known as dengue hemorrhagic fever), which can cause:

Since there is no specific antiviral treatment, prevention is essential, for both travelers and residents. The most effective protection includes the consistent use of mosquito repellent (containing DEET), wearing long-sleeved clothing, and using mosquito nets or staying in air-conditioned rooms, particularly during the rainy season (May to October) when outbreaks are more common.

In addition to bite prevention, vaccination has become a new tool in dengue prevention:

Dengvaxia® (Sanofi): Approved for individuals aged 6 to 45 who have already had a confirmed previous dengue infection. It requires three doses over 12 months. It must not be given to people who have never had dengue, as this increases the risk of severe illness upon first natural infection.

Qdenga® (Takeda): A newer vaccine available for people aged 4 and older, regardless of prior infection. It requires two doses, three months apart, and is increasingly used in high-risk areas. As of 2024, it has been prequalified by the WHO, but may not yet be widely available in Laos.

Because vaccine access is still limited and dependent on individual risk factors and medical history, mosquito protection remains the most reliable prevention against dengue fever. Travelers should consult a travel health specialist before departure to assess whether dengue vaccination is appropriate or available for them.

There is currently no specific antiviral treatment for dengue fever. Management is primarily supportive care, which focuses on relieving symptoms and preventing complications. Patients are advised to rest, stay well-hydrated with water and electrolyte solutions, and take paracetamol (no blood thinners!) to reduce fever and pain. Aspirin and ibuprofen should be avoided, as they can increase the risk of bleeding. In severe cases, hospitalization may be necessary for intravenous fluids and monitoring. Early medical attention is crucial, especially if symptoms worsen after the fever subsides, as this may indicate severe dengue.

BONUS TIP: Some people in Southeast Asia swear by papaya leaf juice to recover faster from dengue fever and science is starting to back them up. Several small clinical studies suggest that papaya leaf extract can help increase blood platelet counts in dengue patients, possibly shortening recovery time and reducing the need for transfusions. But: Results are not consistent across all studies and there’s no standardized dosage. It should never replace medical treatment, especially for severe dengue.

Papaya leaf juice appears to be a promising, safe, and natural therapy for dengue, especially to support platelet recovery and immune function. However, the authors call for larger, high-quality randomized trials to establish standard dosage, formulation, and efficacy (Teh et al., 2022)

The conclusion of another study finds, that Papaya leaf extract appeared to significantly boost platelet and immune cell counts in this patient, suggesting potential therapeutic benefit for dengue—but being a single-case report, broader clinical studies are needed (Ahmad et al., 2011).

Papaya trees grow almost everywhere in Southeast Asia and papaya leaves are widely available. So in case you got dengue fever, it can be a good additional form of treatment to increase blood platelet count.

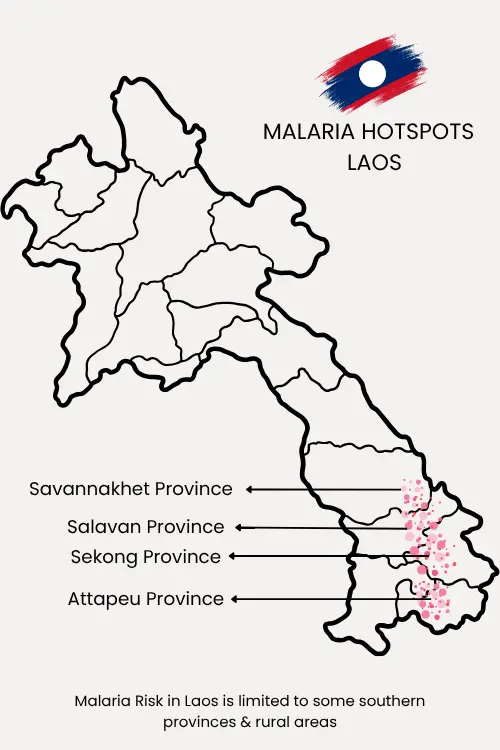

Malaria is still present in some southern parts of Laos, but not a major public health issue anymore. Malaria occurs particularly in remote, forested and border regions, though the overall number of cases has declined significantly in recent years according to the Mekong Malaria Elimination Programme from the WHO. Urban centers and popular tourist areas like Vientiane or Luang Prabang are considered partly malaria-free or low-risk, but malaria transmission mostly occur in rural & remote areas in some southern provinces, especially Savannakhet, Attapeu, Sekong, Champasak and along borders with Vietnam and Cambodia.

The WHO reports, that between 1997 and 2022 Malaria cases have declined from 460.000 cases to only 2300 cases (WHO, 2023). Another study from the Malaria Journal states, that 85% of the Malaria cases in Laos appear in three southern provinces Xekong, Attapeu, Salavan (Kang et al., 2024). In the period from July to September 2024 only 120 Malaria cases were reported in Laos (Mekong Malaria Elimination Programme, WHO, Vol. 27, 2024).

I live on one of those southern provinces and have never heard of a single case of Malaria, but Travelers engaging in trekking or overnight stays in rural areas in the mentioned provinces should take extra precautions.

Malaria in Laos is transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito, which is active at night, typically from dusk until dawn. These mosquitoes prefer clean, still water in shaded rural and forested areas for breeding—making people in remote villages, border regions and forest camps particularly vulnerable. The disease is caused by Plasmodium parasites, with the two most common in Laos being Plasmodium falciparum (more dangerous) and Plasmodium vivax (can relapse). Unlike dengue, malaria is not a disease of cities—risk is low in urban areas but increases significantly during travel or trekking to rural & remote areas in southern provinces. However, it is not common that the typical tourist in Laos ever visits one of the mentioned areas.

P. falciparum infections can be life-threatening if not treated promptly, while P. vivax may stay dormant in the liver and cause relapses weeks or even months later. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent complications.

Symptoms of malaria usually appear within 7 to 30 days after the mosquito bite, depending on the type of parasite. Common symptoms include:

If you develop fever, chills, headache, or flu-like symptoms, especially after spending time in rural or forested areas, you should seek medical attention immediately. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential, as Plasmodium falciparum can become severe within 24 hours.

In larger cities like Vientiane, Savannakhet or Pakse, you’ll find international clinics and hospitals that offer rapid diagnostic tests and effective antimalarial treatment. Do not attempt to self-treat without a proper diagnosis, as the symptoms can overlap with dengue or other tropical illnesses. If it gets worse, you can travel to Thailand for treatment.

For longer stays in high-risk areas, such as rural Sekong, Attapeu or Salavan province, consider asking a doctor about malaria standby therapie, a prophylaxis is usually not needed. Especially for short-term visits or visits in low/no-risk zones or urban areas, a prophylaxis is not necessary.

In most cases, no, Malarone is not routinely recommended for travel in Laos because:

The malaria risk is low, especially in cities, tourist areas, and major towns (like Vientiane, Luang Prabang, Savannakhet, Pakse).

The majority of cases occur in remote, forested, or border regions, especially in the south (Attapeu, Sekong, Salavan) and near the Vietnamese and Cambodian borders.

Malarone can cause severe side effects such as nausea, dizziness, and vivid dreams—which many travelers want to avoid if the actual risk is minimal.

This is not a medical advice! Seek professional medical advice before traveling to tropical countries. Many health professionals recommend a “standby emergency treatment” approach: Bring Malarone with you when staying longer periods in the mentioned affected areas, but only take it if you develop fever and can’t access medical care quickly.

In addition to dengue and malaria, Laos sees occasional transmission of Chikungunya, Zika and Japanese Encephalitis (JE), each with distinct risks and epidemiological patterns.

Chikungunya virus is transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes and was first recorded in Laos during an outbreak in 2012–2013 in Champasak Province. From 2014 to 2020, only sporadic, often imported cases occurred—mainly in Central and Southern Laos—with no country-wide epidemics .

Symptoms begin 2–12 days after infection, include high fever, severe joint and muscle pain, headache, rash, and may lead to chronic arthralgia. Treatment is supportive only, and prevention relies on vector control and repellents.

Zika virus is also spread by Aedes mosquitoes and though serological evidence suggests low-level circulation in Laos, there are no known recent outbreaks. Most infections are mild or asymptomatic, presenting with fever, rash, red eyes, headache, and mild joint pain in symptomatic cases. However, it is a serious risk to pregnant women due to potential birth defects, including microcephaly.

Japanese Encephalitis is caused by a Culex mosquito transmitted virus, circulating year-round throughout Laos—particularly in rural, rice-farming areas with pigs and birds as reservoir hosts. The virus has a 5–15 day incubation period and up to half of severe cases may experience permanent neurological damage, with 20–30% mortality among encephalitis patients. No antiviral treatment exists, but vaccination is safe, effective, and recommended for travelers or residents spending significant time in rural areas.

These viruses are not endemic in Laos like dengue but represent seasonal or localized risks. Integrating repellents, mosquito nets and considering vaccination for Japanese Encephalitits (if necessary), are key for safe living in Laos.

(scroll on mobile devices)

| Virus | Transmission | Symptoms | Prevention | Vaccine Available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dengue | Aedes mosquito (day-biting) | High fever, headache, joint pain, rash | Repellent, long sleeves, mosquito nets | ✅ Dengvaxia (with prior infection), Qdenga (general use) |

| Malaria | Anopheles mosquito (night-biting) | Fever, chills, headache, fatigue | Mosquito nets, repellent, optional prophylaxis | ❌ No |

| Chikungunya | Aedes mosquito (day-biting) | High fever, joint/muscle pain, rash | Repellent, eliminate standing water | ❌ No |

| Zika | Aedes mosquito (day-biting) | Mild fever, rash, red eyes, risk in pregnancy | Repellent, avoid bites, pregnancy precautions | ❌ No |

| Japanese Encephalitis | Culex mosquito (night-biting, rural) | Encephalitis, seizures, high mortality in severe cases | Mosquito nets, vaccine for rural travel | ✅ Yes |

A reliable travel or health insurance is essential when visiting or living in Laos, especially with mosquito‑borne diseases like dengue, malaria, chikungunya, or Japanese encephalitis present in the country. Medical treatment in Laos can vary in quality, and serious cases often require evacuation to Thailand. And that’s something which can quickly become extremely expensive without proper coverage.

For short‑ or mid-term travelers, a flexible travel insurance like SafetyWing is a practical option, offering worldwide coverage and protection against unexpected medical costs during your trip. For expats, digital nomads and anyone staying long‑term, a more comprehensive international health insurance is strongly recommended.

A free consultation with out insurance broker can help you find the best long‑term plan tailored to your needs. Having the right insurance ensures that if you do fall ill with any mosquito-borne disease, you can access quality care without financial risk, giving you peace of mind throughout your stay in Laos and other Southeast Asian countries.

Laos, with its tropical climate and rich biodiversity, is home to several mosquito-borne diseases that pose a health risk to both locals and foreigners. The most prevalent is dengue fever, which is endemic and surges during the rainy season, followed by malaria, which remains limited to remote, forested southern provinces. Other diseases such as Chikungunya, Zika, and Japanese Encephalitis occur sporadically or in specific regions, particularly rural or agricultural areas.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of these diseases, their transmission and symptoms, regional risk differencesand effective prevention strategies. It also discusses available vaccines like Qdenga® and Dengvaxia® for dengue and the Japanese encephalitis vaccine, as well as innovative efforts like the release of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes to control disease spread. With firsthand insights and medical guidance, the guide helps travelers, expats, and digital nomads in Laos better understand the risks and how to stay protected year-round. Also make sure to have travel health insurance to be covered in case of a severe case of any mosquito-borne disease, will give you peace of mind.

Yes. Dengue is endemic in Laos, meaning it is always present. Outbreaks peak during the rainy season (May to October), especially in urban areas like Vientiane. It is the most common mosquito-borne disease in the country and can lead to severe illness upon secondary infection with a different virus serotype.

Yes. Two vaccines exist: Dengvaxia®, which is only for people with a prior confirmed dengue infection, and Qdenga®, which can be given regardless of past infection. However, availability in Laos may still be limited. Preventing mosquito bites remains the most effective strategy.

In most cases, no. Malaria risk is low in cities and tourist areas but present in remote forested southern provinces like Attapeu, Sekong, and Salavan. For short visits to low-risk areas, medication is not usually needed. Travelers to remote regions may consider carrying a standby emergency treatment after consulting a doctor.

Besides dengue and malaria, Laos occasionally reports cases of chikungunya, Zika virus, and Japanese encephalitis. Chikungunya and Zika are rare, while Japanese encephalitis is more common in rural areas with rice fields and pigs. A vaccine is available for JE and recommended for long-term rural stays.

Use mosquito repellent with DEET, wear long-sleeved clothes, sleep under mosquito nets, stay in screened or air-conditioned rooms, and avoid standing water. In higher-risk areas, consult a travel health expert about vaccinations and preventive medication.

share this article: